Census

Census

Censuses are a necessary part of government. Without accurate information about how many people there are, where they are living and what ages they are, it is impossible to plan health services, public transport, taxation and many other essentials of life in an organised society.

The first known censuses were taken in ancient Babylon, almost 6,000 years ago. But they were also carried out by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Indians, Israelites, Chinese and Romans. In all cases, they were closely connected to taxation and public services.

Modern census-taking, based on scientific and statistical principles and recording much more than numbers and locations, began in the late eighteenth century and was firmly established as a necessary part of public administration by the middle of the nineteenth century. The normal practice - still recommended by the United Nations - is for a census to be held every ten years.

Apart from the information supplied by the householders filling out a census return, the nature of the questions asked can also reveal a good deal about the concerns of the government that designed it. For example, US censuses from 1800 to 1860 request great detail about the numbers of slaves in each household. From 1870, after slavery was abolished, these questions are replaced by questions about 'color'. From 1880, when mass immigration became a political issue, the birthplaces of each individual's father and mother are requested.

And in Ireland every census since 1831 has asked for each individual's religion. This is in contrast to censuses in England, Scotland, Wales, Canada and the US, where this question was not asked in historic censuses. Religion, specifically how many Catholics and Protestants there were, was a very, very important issue for governments during much of Ireland's history.

Why take censuses in Ireland?

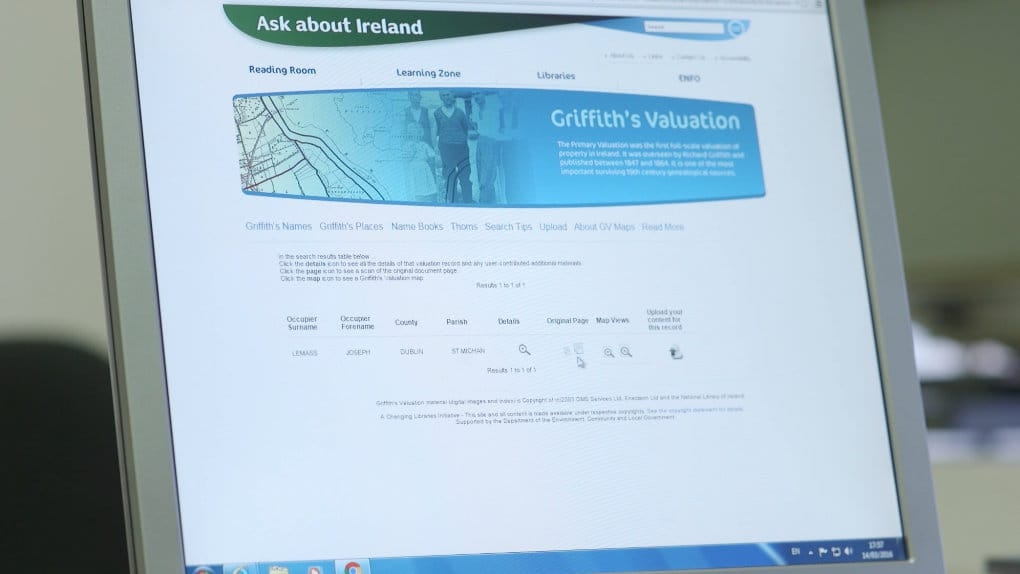

Ireland became part of the United Kingdom after the Act of Union in 1800. Before then, public administration in Ireland was quite unsystematic. After 1800, London found itself in charge of a place about which it realised it knew very little. The early decades of the nineteenth century therefore saw a sustained effort to measure and record Ireland in a way that had never happened before.

The first true census in the new United Kingdom was taken in Ireland in 1821. Earlier headcounts had taken place in England and Wales, but this was the first census that we would recognise as modern, listing names and family relationships, occupations and addresses. It was certainly flawed - the enumerators were paid by the number of returns they produced, a serious incentive to invent - but it was complete for the entire island.

Censuses were then held every ten years, becoming more detailed and comprehensive as Victorian public administration grew in competence and reached into every corner of Ireland.

What happened to the Irish census returns?

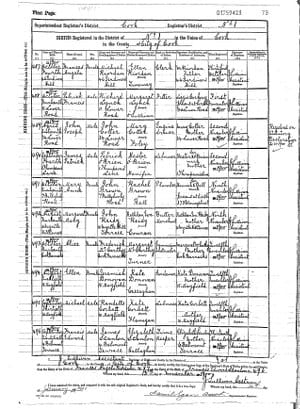

By 1914, ten full censuses had been carried out in Ireland. The returns from 1861 and 1871 were destroyed shortly after they were taken, but there were still no fewer than eight full sets of returns in existence, the earliest four transferred to the Public Record Office, the others still held by the Office of the Registrar-General, the body responsible for census-taking after 1851.

Then things started to go wrong. First, at some point during the first World War, the Registrar-General ordered the 1881 and 1891 returns to be pulped, for reasons that are still unclear.

And then in June 1922, in the bombardment that began the Civil War, the Public Record Office in Dublin was destroyed and every single item held in its Strong Room, including almost all of the four earliest censuses, was obliterated without trace.

The only two censuses to survive in their entirety were from 1901 and 1911. Scraps from the earlier censuses that were not in the Strong Room - out for rebinding, in use in the Reading Room, not yet returned to their shelves - were also spared.

All of the surviving pre-1922 returns are now imaged and freely searchable at the National Archives of Ireland website, census.nationalarchives.ie